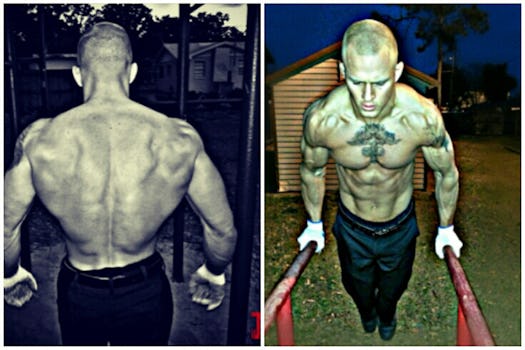

I used to be into heavy powerlifting, but recently moved to a purely bodyweight training regimen.

I noticed a big change in both my physique and strength.

I actually felt a difference in my body; doing my unique exercises opened up a totally new door.

I noticed I was using muscles that I had never even used before.

Believe it or not, all my workouts involve calisthenics circuit routines now. In a circuit, you move from one exercise to the next with little or no rest between moves.

Circuit training doesn’t allow your heart to rest or slow down. It keeps it up consistently throughout your workout allowing you to burn more calories and build conditioning.

I do hundreds of different calisthenics circuits and I never touch the weights. I’ve lost 37 pounds of fat in six months doing my exercises. I went from 202 pounds to a lean 165 pounds.

I get at least 50 messages a day just on my transformation and how I did it.

The best part is, anyone can do it themselves with hard work and dedication.

I’m going to share four of my circuit workouts with you. One is for beginners and can be done at home. Two are for intermediate and advanced exercisers, and one is only for extreme athletes.

Find the workout that’s best for you and, if you stick to it, you will see results in less than two months.

How Long Should You Train For In a Calisthenics Workout?

The At-Home (beginner level), Intermediate, and Extreme Athlete routines shown here should all take 30 minutes or less to complete. The Advanced workout may take as long as 45 minutes. In general, you can save time by trying to move at a brisk pace between exercises and circuits, but give yourself enough rest time so that you can complete your exercises safely and with good form. You can work on reducing rest periods as your conditioning improves over time. Have a timer handy to track the length of your sets and your rest periods; you’ll need one for the Advanced and Extreme Athlete workouts.

How Long Should You Recover After A Calisthenics Workout?

Each of these workouts can be performed up to four times per week on non-consecutive days. Three to four workouts per week is enough. For example, Monday, Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday. You can also combine them, performing the At-Home workout one day, the Intermediate on another, and the Advanced (if you dare!) on a third day. If you feel extra sore or run down on a day you had planned to train, take another day’s rest before your next workout (or perform light exercise or aerobic activity, such as walking/jogging, cycling, yoga, mobility work, etc.).

Calisthenics Vs. Weight Training

The term calisthenics refers to training that uses primarily bodyweight exercises to develop strength, endurance, mobility, and coordination. It’s the kind of exercise that gymnasts and martial artists have done for eons using their own body weight, and while it develops muscle mass too, that’s more of a byproduct. You can expect to get very strong relative to your bodyweight when you do calisthenics training, and master your control of your body in various positions and movements. I.e., you’ll become stable and athletic.

Weight training uses external loads—free weights, cables, machines—to strengthen the body, and while it can develop the same qualities that calisthenics can, it’s better-suited for those who want to build maximum muscle mass, power, and absolute strength. This makes it a potentially better choice for athletes in sports like football, baseball, and track and field. A gymnast will usually be able to do more pullups and pushups than a bodybuilder or powerlifter, but the one who lifts heavy weights can probably move more overall load and will look bigger and stronger. Neither kind of training is superior to the other— both have their advantages, depending on your goals.

For the best, most well-rounded results, include both calisthenics, cardio and weight training in your regimen. You can alternate the styles, spending a few weeks working on one and then switch to another, or you can combine them in the same workout. For instance, you can start with weight training exercises to peak your power and strength, and then finish your routine with bodyweight training that works more on endurance and movement skills.

How To Stretch For A Calisthenics Circuit Workout

Follow the video below for a routine to warm up your entire body before the calisthenics workouts offered here. For more tips on mobility and stretching, follow Onnit-certified Durability Coach Brian Butz (aka @themobilemammoth on Instagram).

1. Lateral Squat to T-Spine Rotation

Sets: 2–5 Reps: 5–10

[See 00:58 in the video above]

Lunge out to your left side and lower your body until your left leg is bent about 90 degrees and your trailing leg is straight. Hold for a moment, and then reverse the motion, twisting your body to get into a lunge position on the right leg, facing that direction.

Plant your left hand on the floor and twist your torso to the right, reaching your right hand overhead.

Repeat the entire movement on the opposite side.

2. Adductor to T-Spine Rotation

Sets: 2–5 Reps: 5–10

[See 01:30 in the video]

Get on all fours and extend your right leg to the side. Use your hands to gently push your hips back so your feel a stretch on the inner side of your right thigh. Allow your foot to roll backward and point upward.

Push your hips forward again and twist your torso to the right, reaching your right arm overhead. Complete your reps and then repeat on the opposite side.

3. Mountain Climber to Hip Flexor Stretch

Sets: 2–5 Reps: 5–10

[See 02:00 in the video]

Get on all fours, and then step your left foot forward, planting your foot outside your left hand. Try to straighten your back so that it’s flat from your head to your pelvis. Relax, and reach back to grasp the top of your right foot.

Gently pull it forward so you feel a stretch on your right thigh and hip. At the same time, extend your back and use your left hand to push on your left knee so you end up in a tall kneeling position.

Hold the stretch for a moment, and then let your right foot go. Repeat the movement on the opposite side. Avoid hyperextending your lower back when you pull on your foot.

4. Shinbox to Hip Extension

Sets: 2–5 Reps: 5–10

[See 03:06 in the video]

Sit on the floor with your left leg bent in front of you and your right leg bent behind you. Press your hands into the floor and push your chest up and out. Now rotate your right leg up off the floor as you rotate your left leg up and to the right, so your body turns and you end up in the same starting position but with your legs opposite. From there, extend your hips so you rise to a tall kneeling position.

Lower your hips back to the floor, plant your hands, and repeat the movement to the other side.

At-Home Calisthenics Circuit Workout

Here’s a bodyweight workout that’s appropriate whether you’re a total beginner to training or you have a little experience with lifting weights but you want to get back to basics with calisthenics training. You can do this routine at home if you have a pullup bar, and it may help to have an elastic exercise band as well, which can help to unload some of your bodyweight and make exercises like chinups and dips easier.

Perform the exercises as a circuit, completing one set for each in sequence. Rest 60 seconds between exercises, and repeat the circuit for 3 total rounds. Except where otherwise noted, do as many reps as possible for each exercise, but stop one short of failure—that means when you feel your form is about to break down. For example, if you’re doing chinups and you get to the eighth rep and feel like you’re slowing down and won’t get a ninth rep with good form, stop the set there.

1. Chinup

Reps: As many as possible

[See 00:49 in the video above]

Use a shoulder-width grip and turn your palms to face you. If you can’t get at least 5 reps on your own, attach an elastic exercise band around the bar and stand in the open loop to unload some of your bodyweight.

2. Dip

Reps: As many as possible

[See 01:00 in the video]

Lower your body until your upper arms are parallel to the floor. If you can’t get at least 5 reps on your own, attach an elastic exercise band to the dip bars and stand (or kneel) in the open loop to unload some of your bodyweight. If you don’t have dip bars, you can use the backs of two chairs.

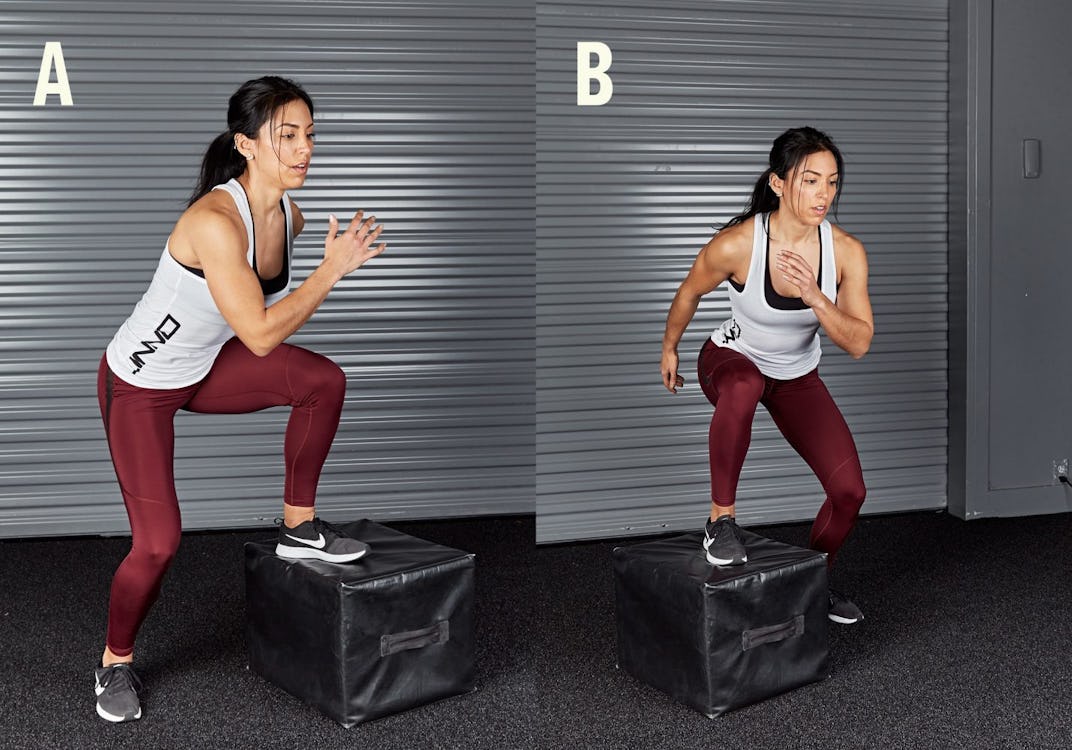

3. Jump Squat

Reps: As many as possible

[See 01:15 in the video]

Stand with feet between hip and shoulder-width and quickly lower your body until your thighs are parallel to the floor. Explode upward as high as you can. Land softly, and reset yourself before you begin the next rep.

4. Pushup

Reps: As many as possible

[See 01:28 in the video]

Place your hands just outside shoulder width and lower your body until your chest is about an inch above the floor. Keep your body in a straight line with your core braced. Your lower back shouldn’t arch and your elbows should point 45 degrees from your torso.

5. Crunch

Reps: As many as possible

[See 02:08 in the video]

Raise your torso until your shoulder blades are off the floor.

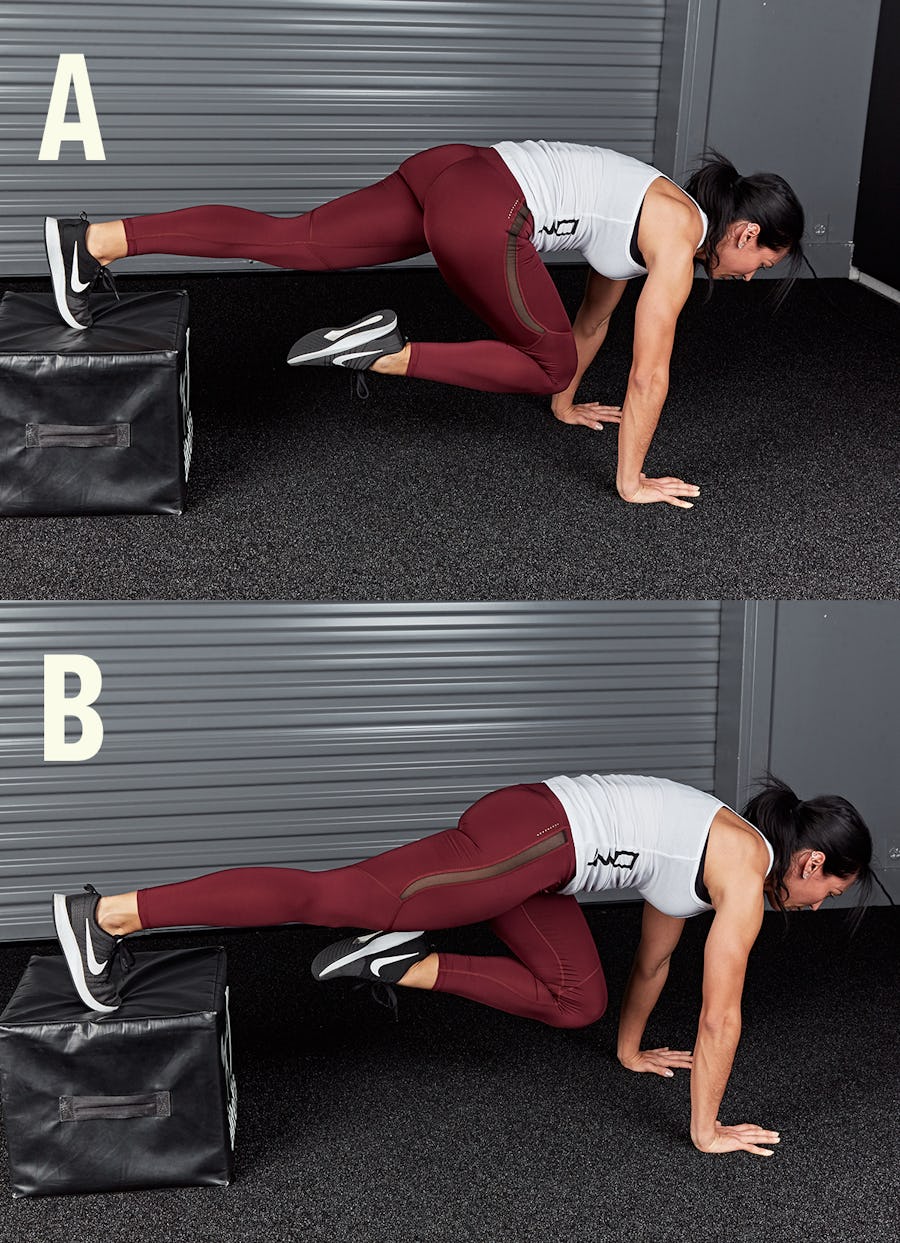

6. Mountain Climber

Reps: Go for 30 seconds

[See 02:19 in the video]

Stand with feet shoulder width and squat down to place your hands on the floor. Now shoot your legs behind you fast so you end up in the top position of a pushup. Jump your legs back up so they land between your hands and then stand up quickly.

BONUS: Jump Rope

Reps: Jump for 30 seconds

[See 02:26 in the video]

If you have a jump rope, jump for 30 seconds, landing on the balls of your feet. Any type of jump is OK, or mix a few together.

Intermediate Calisthenics Circuit Workout

This workout is good for people with a year or more of strength training or bodyweight-only training under their belt. You can do it at home, but you’ll need a pullup bar and some space to run, so a public park or a gym may be more appropriate.

Perform the exercises as a circuit, completing one set for each in sequence. Rest 60 seconds between exercises, and repeat the circuit for 3 total rounds. Except where otherwise noted, do as many reps as possible for each exercise, but stop one short of failure—that means when you feel your form is about to break down. For example, if you’re doing jump squats, you might get to rep 10 and feel like you’re slowing down. If you’re pretty sure you won’t be able to get the 11th rep at the same speed or with a safe landing, stop the set there.

1. Feet-Elevated Pushup On Rings

Reps: As many as possible

[See 00:58 in the video above]

Set the handles of a suspension trainer around shin level and rest your feet on a bench behind you. Suspend yourself over the handles in a pushup position and then lower your body until your chest is just above your hands. Keep your body in a straight line with your core braced.

2. Feet-Elevated Inverted Row

Reps: As many as possible

[See 01:20 in the video]

Set the handles of a suspension trainer low enough so that when you hang from them with arms extended, your body is angled 45 degrees to the floor, or lower. (If you’re strong enough, rest your feet on a bench for an added challenge.) Keep your body in a straight line and brace your core as you pull yourself up.

3. Jump Squat

Reps: As many as possible

[See 01:39 in the video]

Stand with feet between hip and shoulder-width and quickly lower your body until your thighs are parallel to the floor. Explode upward as high as you can. Land softly, and reset yourself before you begin the next rep.

4. Burpee

Reps: As many as possible

[See 01:55 in the video]

Stand with your feet between hip and shoulder width, and squat down to place your hands on the floor in front of you. Jump your legs back into the top of a pushup position, then reverse the motion to come back up to standing.

5. Leg Flutter

Reps: Repeat for 60 seconds

[See 02:38 in the video]

Flatten your lower back into the floor and brace your abs. Extend your legs overhead and then lower them as far as you can before you feel your lower back is about to buckle up from the floor. Begin raising and lowering both legs, alternately, a few inches (as if you were kicking your legs while swimming).

6. Sprint

Reps: Run for 30 seconds

[See 02:58 in the video]

Run as fast as you can maintain for 30 seconds. Other options are to run up a hill, or run in place.

Advanced Calisthenics Circuit Routine

If you’ve been training for a few years and feel pretty strong on bodyweight exercises, give this advanced routine a shot.

Perform the exercises as a circuit, completing one set for each movement in sequence. Set a timer and perform each exercise for 30 seconds. Try to limit your rest between exercises. Do 1–3 total rounds.

1. Crow Pose

Reps: Hold for 30 seconds

[See 00:28 in the video above]

Get into a deep squat position and plant your hands on the floor. Tip your body forward and rest your knees on your elbows. Extend your back and hips so that your bodyweight is supported on your hands, and hold the position.

2. Jump Squat with Rotation

Reps: Jump in the 3 directions shown for 30 seconds

[See 01:02 in the video]

Lower your body into a squat quickly and then explode upward as high as you can. Swing your arms back as you go down, and throw them forward as you jump. Land softly, driving your knees outward. Hop 90 degrees to your right side, and repeat the jump. Hop back to face forward again, jump, and then rotate to face your left side, and jump again. Continue in this manner, jumping in the three different directions. Don’t let your knees cave inward on your landings, and make each jump as vertical as possible.

3. Hindu Pushup

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 01:40 in the video]

Get into pushup position and drive your hips backward as you extend your arms overhead. You’ll end up in a downward dog pose. Now lower your chest toward the floor in an arcing motion, finishing the pushup with your chest facing forward and your hips just above the floor (an upward dog pose). Keep your core braced so that your ribs don’t flare, and avoid shrugging your shoulders. Keep your shoulder blades together and pulled downward as you move toward the floor, and spread them apart as you push up.

4. Candlestick Roll

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 02:30 in the video]

Get into a deep squat and roll backward onto your shoulders. Roll forward again and go into the bottom of a deep lunge with your back knee pointing 90 degrees to the side. The heel of your front foot should stay flat on the floor. Repeat on the other side.

5. Lateral Squat w/ Rotation

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 02:59 in the video]

Shift your weight to your left leg so you feel like you’re sitting into your left glute. Now raise your right knee up and outward, planting your right foot on the floor at a 90 degree angle—both heels should be in line. Lower your body into a squat, keeping a long spine from your head to your pelvis. Alternate sides each rep.

6. Xs and Os

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 03:25 in the video]

Lie on your back and extend your arms and legs to form an X shape. Flatten your lower back into the floor. Perform a crunch, drawing your knees to your chest along with your arms.

7. Planche with Scapular Protraction

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 03:46 in the video]

Get into pushup position and turn your palms around so that your fingers point behind you. Hold your body in a straight line with your core braced and squeeze your shoulder blades together so that only your torso moves closer to the floor. Spread your shoulders apart to raise it back up while you hold your body in position.

8. Jumping Lunge

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 04:16 in the video]

Get into a lunge position—rear knee just above the floor and front knee bent 90 degrees. Jump and switch legs in mid air, landing with the opposite leg forward. Drive the arm that’s opposite the front leg forward on every rep.

9. Lateral Hop

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 04:55 in the video]

Hop side to side, landing with control. It may help to place an object on the floor to jump over.

10. L-Sit Pullup

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 05:10 in the video]

Grasp the bar with hands outside shoulder width. Raise your legs up straight in front of you as you pull your body up until your chin is over the bar.

Extreme Athlete Calisthenics Circuit Routine

This workout is for very strong individuals who feel they’ve mastered their bodyweight on the basic exercises. It will challenge you with different movements you’ve probably never tried before, many of which are borrowed from the routines of gymnasts and MMA fighters.

Perform the exercises as a circuit, completing one set for each movement in sequence. Perform each exercise for the amount of time shown, and rest 30 seconds between exercises. Do 3 total rounds of the circuit, resting as little as possible between rounds.

1. Hanging Somersault

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 00:37 in the video above]

Hang from a pullup bar with hands at shoulder width and raise your knees to your chest. Roll your body backward until your shins face the ceiling, and then reverse the motion.

2. Reverse Curlup

Reps: Repeat for 30 seconds

[See 00:52 in the video]

Lie on your back on the floor and place a block or other light object between your knees. Squeeze your legs to keep it in place. Grasp a heavy or sturdy object with both hands behind your head. Keeping your legs straight, flatten your lower back into the floor and raise your legs up until your hips are off the floor.

3. Modified Front Lever

Reps: Hold for 10 seconds

[See 01:22 in the video]

Hang from a pullup bar with hands shoulder width. Tuck your knees to your chest and roll your body back so your torso is nearly parallel to the floor. Hold the position.

4. Planche with Single-Leg Pushup

Reps: 2 on each side, alternating for 30 seconds

[See 01:44 in the video]

Get into pushup position and turn your palms around so that your fingers point behind you. Hold your body in a straight line with your core braced, and raise one leg off the floor. Maintain this position as you perform two pushups. Switch the leg that’s raised and repeat. Continue until the time is up.

5. Handstand Hold

Reps: Hold for 30 seconds

[See 02:15 in the video]

Get into pushup position in front of a wall and walk your feet up the wall until your torso is nearly vertical. Brace your core so your ribs are pulled down and your torso is a solid column. Hold the position, then walk your feet down the wall slowly to return to the floor.

6. Mammoth March

Reps: Do 1 rep of each lunge, then squat, and repeat on the opposite leg. Continue for 30 seconds.

[See 02:38 in the video]

Step forward with your right leg and lower your body into a lunge position. Step back and all the way behind you to do a reverse lunge. Then step out to your right side for a lateral lunge, come back, and step behind you to the opposite direction for a dragon lunge. Step back until your feet are parallel, squat, and repeat the lunges on the opposite side. Squat again, and repeat the entire sequence until time runs out.

]]>The steel club—the ultimate evolution of the age-old club tool—may be the best training implement you haven’t tried. Here’s what you need to know to start implementing it in your workouts.

What Is A Steel Club?

The club is an offset-loaded weight-training tool, often called a leverage-challenge tool, that works similarly to a kettlebell or steel mace. The bulk of the club’s weight is set at a distance from its handle, making it difficult to stabilize and control. Because of this design, the club lends itself to rotational movements better than perhaps any other piece of equipment (which we’ll discuss in depth further down). Clubs range in length from about one foot to a little more than two feet, and generally come in weight increments ranging between five and 45 pounds.

“The club was our first tool and our first weapon, going back to pre-historic times—think, caveman,” says Shane Heins, Onnit’s Director of Fitness Education, and a steel club coach. “It helped us hunt and fight. People figured out that swinging a club increased the torque on it, and that increased the force it could strike with and the damage it could inflict. So armies learned to swing clubs in battle.”

Over time, warriors realized that swinging clubs—and maces, which developed the same way—strengthened their bodies, and they began formalizing club and mace use for sports training and fitness purposes. Every continent had its own version of the club. To this day, some still call the tool an Indian club, or Persian club (sometimes referred to as a “meel”), as the Indians and Iranians (not least of all the Iron Sheik) did so much to popularize it. In modern times, martial arts fitness expert Scott Sonnon has perhaps been the club’s most vocal champion, helping to spread awareness of club training in the Western world with the popularity of his Clubbell® line over the past 20 years.

Traditionally, clubs were made of wood, but that made progressing to heavier weights problematic. To get a heavier club, you had to upgrade to a bigger piece of wood, making the club cumbersome and difficult to travel with. Due to their greater density, modern-day steel clubs offer heavier weight in a more compact size.

What are the Benefits of Steel Club Training?

As with the kettlebell, steel mace, or any other tool where the weight is offset from the handle, the club presents a number of challenges that you can’t get to the same degree with more conventional equipment. It also has a few features that make it unlike any other implement you can use.

Training with the steel club helps you¦

1. Build Core Strength

Kettlebells are praised for promoting core strength due to their offset load. The weight is positioned at a distance from the handle, so it’s harder to stabilize, and your body must call on numerous muscles to keep you in alignment. The club takes this to the next level, as the weight is displaced even further at the end of a long lever.

Imagine holding a heavy weight right in front of your chest. It’s close to your center of mass, so you have about as much control over it as you possibly can. Extend the weight away from you, however, and you’ve reduced your leverage advantage. Now it’s harder to lift the load, especially in different planes (say, in a circular fashion as opposed to straight up and down). All club exercises put you at a significant leverage disadvantage, which is bad for making workouts feel easy, but great for activating muscle—especially in your abs and throughout your back.

2. Build Rotational Strength

The leverage disadvantage and shape of the club really feed into its greatest feature—allowing you to train rotational movements.

“Our body works in rotation all the time,” says Heins. For example, swinging a bat, throwing a ball, lifting heavy groceries out of your car, or wrestling with your kids. Some of the best steel club exercises are swinging and spiral patterns that force you to stabilize your body over a long range of motion, and develop power in the rotary plane.

“We also need to be able to resist rotation when it isn’t wanted,” says Heins. “When you’re walking, and you pick one foot up, forces act on it to try to twist it in one direction or the other. When you’re squatting with a barbell, you think you’re going up and down, but there’s rotational force acting on your shoulders, spine, hips, knees, and feet. The club highlights this resistance, and it helps you create greater stability.” Because of its dimensions, doing something as simple as a squat while holding a club is difficult to accomplish without bending or twisting to one side (rotation). But, over time, you’ll learn to move in exactly the planes you want, and the resulting stability will translate to other exercises and athletic movements.

Similar to unilateral exercises, “the club also shows you which of your sides is stronger,” says Heins, “so you can begin to correct the imbalance between the left and right halves of the body.”

3. Build Grip Strength

When you train rotation, you create centrifugal force. As a lever moves around an axis, it wants to pull away from that axis and move outward. In addition to having a thick handle and an offset load, the club is tough to grip because it wants to fly out of your hands when you swing it. “The steel club is great for building a grip that’s really alive,” says Heins. “You can’t just clamp down on it like you do a barbell before a 500-pound deadlift. Wherever you’re holding or moving it, the club is always pushing down or pulling away from you, so you need the dexterity and articulation and sensitivity, in combination with appropriately applied tension, to hold on and control it.” With this in mind, imagine how club training could help a grappler who needs to hang on to an opponent’s gi, a construction worker who hauls heavy materials up a scaffold with a rope, or a fisherman trying to reel in a fighting marlin.

“When you use a club, you have to feel the load transition from between your thumb and forefinger to the pinky and palm of your hand,” says Heins. “The information it sends to your central nervous system is constantly changing.”

The steel mace works the grip in a similar fashion, but the club is harder to hold on to. The handle is shorter, giving you less surface area to grasp. It’s easy to regress the challenge on a steel mace exercise by holding the handle nearer to the ball on the end, or widening your grip, which increases your control. But the load on the club is elongated, and more offset. You have a lot less handle to spread your hands apart on, and gripping the fat end totally changes the nature of the load. It can sometimes feel like your only option is to hold on for dear life. Sound scary? Take it slow, and it’s not as hazardous as you may think. (See Steel Club Safety below.)

4. Decompress Your Joints and Tissues

Most weight-training exercises tighten your body up, literally. Think of what happens to your spine when you do a back squat: the bar rests on your back, shoving your vertebrae closer together. When you press heavy weights, your shoulders and elbows get squeezed. Continually compressing your joints and shortening the muscles that act on them can lead to pain and loss of flexibility, but the steel club can help to alleviate both.

“You have to pull back on the club a bit as it swings,” says Heins, lest you want the centrifugal force to rip it out of your hands. “That creates some traction in your wrists, elbows, and shoulders, which allows fluid to pass through them, helping recovery. You can strengthen a joint with traction just like you can with compression. Pulling it apart makes the muscles and connective tissues work to hold the joint together, and it’s a nice counterbalance to compressive forces you get in your other training.”

Heins says to think of club training like an accordion. “If you squeeze it, you’re only getting half the music. You have to pull the ends apart again to play a song.”

Traction and rotation also have the effect of helping your muscles into new ranges of motion they wouldn’t otherwise explore. Look at a pullover exercise (see the workout below) with the club, in which you hold it vertically and lift it over your shoulder and behind your back in an arcing motion. The weight of the club will help to stretch your triceps, lats, and shoulders as it moves downward behind you. At the same time, holding your ribs down with your core tight to maintain good spine and hip alignment trains your core. You get stretching and strengthening in one movement. How’s that for training economy?

Big weightlifters and powerlifters often report that working the club into their routines helps to open up their shoulders and backs, adding longevity to their competitive careers and easing aches and pains.

5. Get More Out of Light Weight

The handle, the offset load, and the rotational nature of club training make it virtually impossible to use heavy weight, and that’s perfectly alright. If you’re expecting a 10-pound club to feel like a 10-pound dumbbell, get that thought out of your head right now.

“The top-end weights we work with are 35 pounds,” says Heins. “That’s super heavy for club training, but it’s still only 35 pounds of overall load, so even when you get strong on the club, it isn’t hard to recover from. It’s certainly not like recovering after a one-rep max squat with 400 pounds.” Heins notes that doing a long session of club training might leave you mentally zonked, similar to how you’d feel after taking a final exam, because the club requires so much nervous system activation. But it’s too light to leave you physically wrecked for days. For athletes who need to compete frequently, it’s helpful to have a tool that lets them train hard and bounce back fast.

Light weight also makes clubs highly portable. If you’re planning a road trip that will take you away from your gym, clubs can fit easily into the car, providing you with a workout you can do anywhere from a hotel room to an empty parking lot.

6. Make Training Fun!

“I’ve taught training certifications for the club all over the country,” says Heins, “and every time people walk in and pick up a club for the first time, it’s always funny. They think it’s going to feel like a baseball bat or a bowling pin, and then you watch them have to put it down right away because they realize they can’t control it. They take a step back, and then try again.”

To say club training provides a novel workout experience is a given, but it also taps into a primal instinct in us all that’s inherently fun. Clubs can even be used for creative expression. As you master club exercises, you can begin to transition from one to the next seamlessly, creating what’s known as a flow. There’s no wrong order or movement, per se, you just move gracefully from one position to the next, working your whole body in the process. Workouts then become more like warrior dances than weight training.

What Club Should I Buy?

As mentioned above, steel clubs are denser than wood, so they offer easier handling for a wider array of loads (plus, they take up less space). We recommend starting with steel that has a powder-coated handle. Some club handles have knurling (rough texture, same as you see on barbells), which makes for an easier grip, but they can tear up your hands over time—especially if you do a lot of swinging, where the club is pulling away from you with centrifugal force.

Other clubs have handles that are completely smooth, which Heins says presents an even worse problem. “When you sweat, the handle becomes slick,” he says, “which can turn the club into a missile.” The powder coat on Onnit’s clubs provides just enough friction for the club to change positions in your hand without you losing control of it, and it won’t chafe your palms in the process. Additionally, a club should have a knob on the end of its handle—where the pinky end of your grip gets firm purchase—to help stop your hand from sliding back off it.

Heins recommends men start with a pair of 15-pounders and a single 20 or 25-pound club, and says most women will do well with one pair of 10 pounders and a single 15 or 20-pound club. Most of your club training will be done using both hands on one club to start, as this provides the greatest stability. As you progress, you’ll find that exercises done above the waist (such as presses and pullovers) are hardest when utilizing a club in each hand. Those that are done below the waist (swings and leg drivers) are easier when done with a club in each hand versus two hands on one.

How To Warm Up For a Steel Club Workout

Use the following warmup drills to increase mobility and prepare your body for training. Perform 5 reps for each exercise in sequence, and repeat for 3 total rounds.

- Kneeling Spinal Wave (See 00:42 in the video below.)

2. Kneeling Arm Thread (02:17)

3. Kneeling Hip Flexor Twist (03:43)

4. Clasped-Hand Elbow Rotation (04:45)

5. Pullover Spiral Down (06:35)

3 Steel Club Exercises You Have to Try

Experiment with steel club training by incorporating the following exercises into your workouts wherever you see fit. The spiral lift around is great for improving shoulder mobility, and can help to stretch the wrist flexor muscles, which can cause elbow pain when tight. That makes it a good choice before an upper-body training session as part of your warmup, or after a workout to help you lengthen the muscles again.

The side pullover opens up your shoulder and lat, and helps you maintain a tight core position, making it a natural for inclusion in any kind of ab training you do. Lastly, the front swing can be used anywhere you would normally do a kettlebell swing or other deadlift/hinge movement. Suggestion: try it as a finisher at the end of a session, combining short rest periods and high reps to get your heart rate soaring (once you’re experienced and familiar with the movement, that is).

Directions: In your first session, take it slow, and focus on your technique so that you learn the exercises correctly. Perform each for time rather than reps, starting with 30 seconds. So you’ll do reps for 30 seconds straight and then rest. On the spiral lift around and side pullover, work for 30 seconds on one side, and then switch sides and repeat. Perform 3 to 5 sets for each movement.

Spiral Lift-Around

Step 1. Stand with feet between hip and shoulder-width apart, and hold a club at your side in your left hand. It should point vertically to the floor below. Tuck your tailbone so that your pelvis is parallel to the floor, brace your core, and squeeze your glutes. Draw your shoulders down and back—think “proud chest.” Maintain this body position throughout the exercise.

Step 2. Begin raising the club straight up in front of your body, pulling from your elbow and allowing the weight of the club to bend your wrist and stretch your forearm. Let the weight of the club pull down as you continue moving the club around the back of your head, and lower the club back to your side, extending your elbow as it comes down. The end of the club should point to the floor throughout the movement.

Try to keep the club as close to your body as you can during the exercise without bumping into it. Heins says to visualize the club as a candle that’s floating around your body—keep it vertical and control its path.

Side Pullover

Step 1. Hold the club with the end pointing upward, and your elbow bent 90 degrees. Turn your arm so that your knuckles point out 90 degrees from your torso with your elbow by your ribs. Maintain the tight core, pelvis position, and proud chest described above.

Step 2. Reach the club over and behind your head, as if you were raising it to deliver a blow. Turn your head so that your eyes can focus on your arm. Swing the club back down to the start position by driving your elbow next to your ribs until the club is pointing vertically again.

As you raise the club on each rep, allow the weight of it to pull your elbow back and stretch your triceps and shoulder, but don’t relax anything. You may find that your range of motion increases over the course of a set. Bring the club down with force, but not so fast that you can’t control its descent and lose alignment.

Front Swing

Step 1. Hold a club in each hand and, keeping your head, spine, and pelvis in a straight line, swing the clubs down and back behind you at a 45-degree angle as you hinge at the hips.

Step 2. Drive your hips back as far as you can without losing alignment, and then explosively extend your hips to stand tall. Use the momentum to swing the clubs up to eye level. Control the downswing to go back into the hinge and repeat for reps.

Beginner Steel Club Workout

The following routine works well on its own as a fat loss-focused conditioning workout, or (if done for only 3 rounds only) a finisher at the end of a heavy training session. If doing the former, perform it three times per week on non-consecutive days (Monday, Wednesday, Friday, for instance).

Directions: Perform the exercises as a circuit, so you’ll complete one set of each movement in turn. (For unilateral exercises, work one side and then the other before going on to the next exercise). At the end of the circuit, rest 45 seconds. Repeat for 3–5 total rounds.

Instead of aiming for a specific number of reps, you’ll perform your sets for time. Complete as many reps as you can in 30 seconds, and aim to perform one more in the same amount of time each time you repeat the workout, or perform the set with better form and greater control. Don’t rush to get as many reps as possible; focus on perfect execution.

1. One-Arm Pullover

(See 01:20 in the video above)

Reps: Work for 30 seconds (each side)

Step 1. Hold the club in front of you with the end pointing upward, and your elbow bent 90 degrees. Tuck your tailbone so that your pelvis is parallel to the floor, brace your core, and squeeze your glutes. Draw your shoulders down and back—think “proud chest.” Maintain this body position throughout the exercise.

Step 2. Reach the club over your shoulder and behind your head, as if you were raising it to deliver a blow. Swing the club down to its starting position by driving your elbow forward again and down next to your hip, so the club is pointing vertically again.

As you raise the club on each rep, allow the weight of it to pull your elbow back and stretch your triceps and shoulder (but don’t relax anything). You may find that your range of motion increases over the course of a set. Bring the club down with force, but not so fast that you can’t control its descent and lose alignment.

2. Double Leg Driver

(See 02:46 in the video.)

Reps: Work for 30 seconds

Step 1. Stand two clubs on the floor so they sit vertically, a little outside shoulder width. Stand just behind them with a hip to shoulder-width stance, and, keeping your head, spine, and pelvis in a long line, hinge your hips back and bend your knees so you can reach down and grasp the clubs by their handles.

Step 2. Tip the clubs back toward you and extend your hips and knees enough to pick the clubs off the floor and allow them to swing back behind your body.

Step 3. Reverse the momentum and swing the clubs in front of your legs, bending your knees to decelerate them. The range of motion is fairly short. Continue swinging the clubs in this pendulum motion, bending your hips and knees to power the movement. Do not allow your hips and knees to lock out at any time, and maintain a proud chest position and alignment from your head to your pelvis.

3. Two-Hand Front Press

(See 04:44 in the video.)

Reps: Work for 15 seconds with right hand on top, then 15 seconds left on top

Step 1. Stand with feet between hip and shoulder width and hold one club with both hands to the right side of your torso. Your right hand should be on top of the left, and your left should be at the bottom of the handle.

Step 2. Keeping a proud chest, level pelvis, and shoulders square with your hips, press the club straight in front of your chest until your hands are at eye level and your elbows are locked out.

4. Mountain Climber to Down Dog

(See 06:28 in the video.)

Reps: Work for 30 seconds

Step 1. Get on all fours on the floor. Your hands should be directly under your shoulders and your knees under your hips. Your toes should also dig into the floor. Tuck your tailbone so that your pelvis is perpendicular to the floor, and brace your core. Draw your shoulder blades down and together (“proud chest”).

Step 2. Try to maintain your shoulder and hip position as you step your left leg forward and place your foot on the floor to the outside of your left hand. Take a second to retract your shoulders and extend your hips after the rep. Return your leg to the all-fours position, and repeat on the opposite side.

Step 3. When you’ve done the mountain climber on both legs and returned to the all-fours position, push your hands into the floor, extend your knees, and drive your hips back into downward dog. Your head, spine, and tailbone should form a straight line as you balance on the balls of your feet. From there, you can pedal your feet, extending one knee at a time to help loosen your hamstrings. Afterward, return to all fours to begin the next round of mountain climbers.

Steel Club Safety

There’s no denying that the club was originally created to bash things over the head, so we understand if you’re a little reluctant to start swinging it around your living room near your spouse or children. But with a little practice, you’ll see that the club poses no more danger than any other piece of exercise equipment—and maybe even less. Consider this: you’ll never get trapped under a 400-pound squat with it and have to call spotters to pull it off of you.

Heins offers the following safety tips: “Keep your eyes on the club at all times. Turn your head and follow it wherever it goes. When you feel your hands get sweaty, or you’re losing your grip, or you notice your form is starting to break down, end the set and put the club down. There’s no ’just one more rep!’ with club training. Also, be aware of your surroundings and make sure you give yourself space.”

]]>

What Is A Box Jump?

While the exercise does clearly involve jumping from the floor onto a box, it’s not quite as simple as it seems. Not any box will do, and the object isn’t just to get up on top of the surface by any means necessary.

The box jump is a low-level plyometric exercise. That is, it trains the muscles’ stretch reflex to develop explosive power. You quickly lower your body into a half-squat to stretch the glutes and hamstrings, and then use the resulting release of elastic energy to help power you up in the air. So as not to come down too hard, the box is there to break your fall, but it also teaches you to land like a cat—decelerating your body mass and absorbing the force of your jump. These skills are highly valuable to athletes who jump and sprint, so the box jump is a staple in many sports training programs.

At the same time, because it’s not particularly complex or dangerous to perform (if done as intended), the box jump can be done by recreational gym rats who want to add a bit of power training to their routines.

The boxes used can vary in height from a few inches to a few feet, and can be constructed of hard wood, rubber, firm padding, and even steel. Whichever kind you have access to, make sure you start with one that’s not too high (more about this below) and offers a stable surface for your feet to land on—and an even base that doesn’t wobble. Some boxes have fairly small foot surfaces, so, in general, the wider or larger the platform you have to jump on to, the better. (You’ll have less chance of missing it!)

How To Do The Box Jump

Before we get into how to execute the jump correctly, let’s go over a few ground rules for safe box jumping. You’ll also want to check out the five progressions for building up to a box jump from Onnit Director of Fitness Education Shane Heins, beginning at 1:03 in the video above.

Use A Moderate-Sized Box

First of all, be conservative with the height you choose. You should warm up on boxes that are very low to the ground—just a few inches to a foot or so high—and do your work sets with a box that’s only around knee height. Twenty-four to 30 inches high is plenty for all but the most experienced jumpers. Yes, we know you see people jumping onto 50-inch boxes and higher on YouTube and Instagram, but believe it or not, most of them are just trying to impress you, and they aren’t using good form.

The depth you squat to in your takeoff and your landing should be almost the same. That is, you should be landing in approximately a half-squat position, or where your knees are bent about 45 degrees. If you land so deep that your knees are practically to your chest and your lower back is rounded, the box is much too high!

Think about it like this: the point is to build athletic power. If you’re a football player exploding off the line of scrimmage, would you start in the bottom of a squat? Do you bend your knees 90 degrees to take a jump shot in basketball? Do sprinters curl up into a ball before they take off down the track at the sound of a starter’s pistol? Of course not. The goal of a box jump isn’t to leap as high as possible—it’s to train the mechanics that let you develop power when it counts.

Stand Far Enough Back

It matters how far away from the box you set up. Stand back a few feet and extend your arms so that your fingertips touch the box when you reach forward with both hands. That represents the distance that should exist between you and the box when you’re about to perform your first rep, so make a note of it and stand in that spot when you begin your set. Respecting this space ensures you won’t catch your fingers on the box during your upswing when you propel yourself upward into the air. It’s also a good distance to prevent you from overjumping your target and tipping the box forward when you land.

Swing Your Arms Up

Speaking of upswing, understand how much your arms contribute to your jumping momentum. Your arms should swing down by your sides as you descend into the half-squat—the mechanics are somewhat like compressing a spring—and then swing upward with force as you jump. Many people do the opposite, driving their arms down toward the floor as they extend their hips and legs. While this may make you look like a human rocket ship, it’s utterly pointless in jump training, as it does not transfer forces from the floor and through your body to facilitate height.

Land With Control

You know the old saying, “What goes up must come down,” so we have to talk about how to land. Your landing should be quiet and soft. Coming down like a ton of bricks puts a lot of stress on the joints of the lower body and can cause injury. Also, as mentioned above, one of the benefits of a good box jump is learning to slow the force of your movement down, so try to stick your landings like a gymnast. If you find that you’re landing hard and loudly, guess what? The box is probably too high.

Step Down From The Box

Lastly, don’t jump off the box to return to the floor between reps. STEP down off it. Jumping down is the most common box jump technique mistake, and it’s a dangerous one. There’s no benefit to jumping backward off a box, and even at fairly low heights, it can injure your Achilles tendons. (Yes, advanced athletes sometimes jump backward to dismount the box, but we don’t recommend it for folks reading this article.) Set a smaller box, bench, or step next to the box you’re jumping onto and use it as a staircase to get down (if the box you’re jumping on is too high to comfortably step down from directly).

With all these caveats and details out of the way, here’s a step-by-step guide to performing the box jump movement.

Step 1. Set a box on the floor that’s roughly knee height. It should be high enough to provide some challenge but not so high that you can’t land safely. Twenty-four to 30 inches should do it. Extend your arms straight in front of you and stand at a distance that allows your fingertips to touch the edge of the box.

Step 2. Stand with your feet about hip-width apart. (If you deadlift, your deadlifting stance should be about right.) Quickly dip your hips, bend your knees, and swing your arms back to gather power.

Step 3. As soon as you feel your body drop into a half-squat position, explode upward, extending your hips and knees and throwing your arms up and forward to jump off the floor.

Step 4. Land softly in the middle of the box with both feet at the same time. Step down from the box carefully and take a moment to set up for the next jump.

What Muscles Are Used In A Box Jump?

The box jump is a major compound movement that requires a transfer of energy through the entire body, so you can pretty much point to an anatomy chart at random and land on a muscle that’s involved in the exercise in some way. Of course, the quads, hamstrings, and glutes are the prime movers, creating the hip and knee extension that lifts you off the floor, and your shoulders work to drive the upswing of your arms, which helps to propel you upward.

However, because you don’t load the body like you do in a squat, deadlift, or other resistance exercise, you probably won’t feel sore in these muscles the next day, and you won’t see size gains in them from jumping alone. The box jump doesn’t create a great deal of muscular tension, or maintain that tension for a length of time, so it’s not going to build bigger muscles. Using it in place of a leg exercise for muscle mass is not a good idea.

You may be surprised, however, to find that your deep abdominal and oblique muscles are in fact sore a day or so later. That’s indicative of how involved your core is in transmitting forces to your arms for the takeoff. Remember that the goal of box jumping is power, and the result is a highly trained chain of faster, more explosive muscles that work together as a unit.

Best Box Jumping Exercises

Most of the time, you should practice box jumps with a 24–30-inch high box, using the technique described above. Three to five sets of three to five reps is a good general prescription for power gains, but end each set the moment you feel yourself slowing down or losing control of your landing.

Occasionally, to test yourself, you can use a higher box and attempt bigger jumps that might cause you to land deeper than a half-squat. In this case, you can work up to sets of three, two, or just one all-out jump. But for safety’s sake, do this sparingly, and have a spotter handy in case you stumble on the box. One to three times a week is enough frequency for box jumps.

Please be cautious. Unlike with strength training, where you need to add weight or reps on a semi-regular basis to keep making gains, progressing jump training isn’t so linear. Most athletes don’t need more than a moderate-height box, so don’t think that because you leapt up onto a 24-inch box last week, you need to use a 25-inch one this week. If you get to the point where box jumps feel easy at a certain height, work on jumping higher and landing on the same-size box before you bother to increase the elevation. Then, as explained, you can sporadically test your training by attempting higher boxes.

If you’ve done CrossFit WODs or attended a HIIT (high-intensity interval training) exercise class, you might have been instructed to do box jumps as part of a circuit or conditioning drill, using high reps and short rest periods. We suggest that you don’t train like this with box jumps. Explosive exercises and high repetitions don’t mix. That is, power movements like the box jump must be done for lower reps to prevent your form from breaking down due to fatigue. And you simply can’t generate the same explosiveness on a 10th jump as you can on the first three of a set, so high reps don’t suit the goal. Box jumps should also be done with longer rest periods for this same reason—two minutes or more between sets.

If you want to get an endurance boost from your training, you can get it with any number of other, safer exercises. That said, if you’re determined to mix power and conditioning in the same session, we have a safe plan to do so below under HIIT Box Jump Workout.

The earlier in your workout that you do box jumps, the more power and height you’ll be capable of getting. But realize that the box jump does cause some impact on your joints. You also shouldn’t do any kind of fast movement without thoroughly warming up your muscles first, and even a great mobility routine done at the start of your workout may not be enough. Therefore, we suggest placing box jumps toward the beginning of your session, so you’re fairly fresh when you do them, but not cold. For instance, you might do them as your second or third exercise, after a few sets of hamstring and glute work. Leg curls, hip thrusts, or glute-ham raises will pump blood into the posterior chain (the muscles on the back side of the body) and lubricate the hips and knees.

There are other exercises you can do to that sometimes don’t require a box, or even a jump, but will support your box jump training and improve your overall jumping ability. By choosing movements that train the upper body to generate upward force, or that strengthen the posterior chain, you can tighten up the component mechanics that make for gravity-defying leaps.

Weighted Jump With Kettlebell

See the video above at 0:25

Step 1. Place a kettlebell on the floor and stand with feet hip-width apart. Get into a half-squat, as if you were winding up for the box jump—you should be able to reach the kettlebell handle from that position. If the weight is too low, elevate it by resting it on a weight plate or mat. Now deadlift the kettlebell so you’re standing tall.

Step 2. Quickly dip your hips and knees as if jumping, lowering the kettlebell to just above the floor (don’t let it smack into the platform you created), and then explode up. Don’t worry about jumping high, just focus on the power of your explosion. Your feet may rise off the floor, but it’s OK if they don’t. Land softly, reset, and repeat. Do 3 sets of 3–6 reps.

Weighted Stepup

See the video at 1:22

The stepup can help familiarize you with the use of a box while building the glutes, hams, and quads. You can do it with dumbbells, kettlebells, a barbell across the back of the shoulders, or a weighted vest.

Step 1. Hold onto your weight and place your foot on a box or bench. It should be high enough so that your thigh is about parallel to the floor when the foot is resting on it.

Step 2. Drive through your heel to step up onto the bench without letting your rear leg rest on it—let it dangle behind you. Step back down, starting with the trailing leg. Do 3 sets of 8–12 reps.

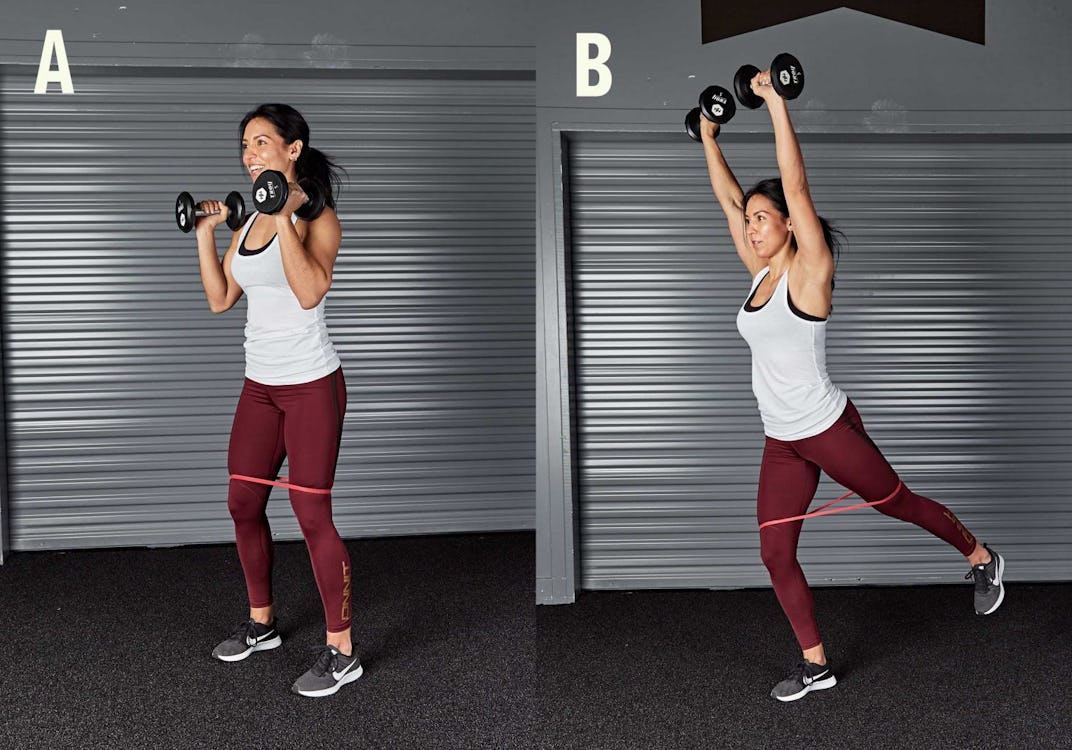

Push Press

See the video at 1:45

Doable with a barbell, kettlebells, or dumbbells, a push press is just an overhead press that uses the legs for assistance. By dipping the knees, similar to how you move in a jump, and then driving up explosively, you can press more weight overhead, which makes the exercise effective for upper-body strength as well as generating power from the ground up. Push pressing is also a great way to learn to keep your body tight and braced. If any muscles are relaxed, you won’t be able to move the weight effectively.

Step 1. Hold the weight at shoulder level and stand with feet about hip width. Brace your core.

Step 2. Drop into a quarter-squat, initiating the descent by bending your knees. Keep your head, spine, and pelvis in line so your back is flat and your eyes and head are forward. You don’t want to turn this leg drive portion of the lift into a squat, so only bend your knees enough to get some momentum, and don’t hinge your hips too much. Imagine yourself doing the move against a wall and sliding your torso up and down it—you should be that upright.

Step 3. As soon as you’ve dipped, extend your hips and knees explosively to stand up straight, driving through your heels, and simultaneously press the weight straight overhead. You’ll need to push from your shoulders and triceps, but with a strong and quick leg drive, most of the power for the press should be provided by your lower body. Keep your core tight throughout the move so your spine is stable and safe. Lower the weight back to your shoulders, take a moment to reset, and then begin the next rep. Do 3 sets of 5–10 reps.

HIIT Box Jump Workout

We’ve established that box jumps should be used conservatively and for athletic performance, but we can’t deny that they spike the heart rate and involve almost every muscle in the body, so we understand if you’re tempted to use them in a conditioning workout that burns calories and boosts endurance.

A way to do this safely is to perform a low-rep EMOM, meaning that you set a timer and perform a set of jumps every minute on the minute. Find a fairly low box—low enough that you know you won’t have trouble landing on it even if you’re tired—and start the clock. Do three jumps, and then rest for the remainder of that minute. When the timer reaches 1:00, do another set. So let’s say the three jumps takes you 15 seconds to do; you’ll get 45 seconds to recover.

Continue this for 20 minutes. It may seem easy for the first five minutes or so, but those short rest periods will catch up with you. This kind of workout probably won’t do much for speed and power, but it can serve as cardio.

If you’re a recreational gym-goer who mainly trains for a better physique and functional strength, but you’d like to add another athletic component to your workouts, incorporating box jumps before your biggest lift of the day can help to prime your nervous system. This can improve your performance on lower-body compound exercises like the squat and deadlift by supporting the recruitment of your fast-twitch muscle fibers. A few sets of box jumps done prior to a big barbell lift won’t fatigue you for the heavy training, but it may allow you to lift heavier and with better form.

Another option is to combine box jumps with a barbell movement, doing the two back to back. This is called contrast training, and it’s a method research has shown can maximize power development in athletes.

In a contrast set, you might do deadlifts with 80% of your max for a set of five (you should have at least a rep or two left in you; don’t go to failure), and then take about 30 seconds rest—during which you can walk over to the box. Now do a set of three jumps at a challenging height. Rest three to five minutes, and repeat for three to four total sets. This is stressful training, so it should be your only exercise for the session, and you should only do contrast training for three weeks at a time.

]]>

What’s the whole truth, bottom line, and final answer on abs? We’re about to clear up all the misconceptions. Consider the following your tome on ab training.

What Muscles Make Up The Abs?

The term “abs” can refer to all the muscles of the midsection, ranging from the deep core muscles that stabilize your spine to the obliques on the side of your torso that help you twist your shoulders and hips and bend to each side. But when most people say abs, they mean the rectus abdominis, more popularly known as the six-pack muscle.

The rectus abdominis originates on the pubic bone and stretches up to the xiphoid process (the bottom of the sternum), as well as the cartilage between the fifth, sixth, and seventh ribs. It works to bend the lumbar spine forward (spinal flexion), pull the rib cage down, and help stabilize the pelvis when you’re walking. When an individual is very lean with well-developed musculature, the rectus abdominis can appear to be six distinct muscles, but it’s only one. The six-pack look is due to a web of connective tissue that compartmentalizes the muscle. Whether someone has a six pack or an eight pack comes down to genetics alone—it’s the way nature shaped their abs—and has nothing to do with training or diet. (For all his gargantuan muscles, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s abs were always comparatively less impressive; he famously sported only a four pack!)

How Is Working Your Lower Abs Different From Upper Abs?

(See 00:30 in the video above.)

Bodybuilders have long believed that exercises that bring the ribs toward the pelvis (crunch variations, for example) work the upper portion of the rectus abdominis, while movements that do the reverse—lifting the pelvis toward the ribs—train the lower portion. Scientists and some trainers, however, have disputed this, arguing that, since there’s only one rectus abdominis muscle and its function is pretty simple, any movement that brings the ribs and pelvis closer together is going to work the whole muscle.

So who’s right?

A study from the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research measured rectus abdominis activation across six different ab exercises, concluding that, while some of the moves worked the muscle more than others, none showed much of a difference in which part of the abs (upper or lower) was activated. Still, other research has shown the opposite. One trial found that the old-school curlup worked the upper portion of the muscle to a greater degree, and the posterior pelvic tilt (basically a reverse crunch, in which the tailbone is tucked under, lifting the pelvis toward the upper body) favored the lower abs—just as the bodybuilders have claimed for years.

So far, the correct answer seems to be a little from Column A and a little from Column B. In his 2021 book, Science and Development of Muscle Hypertrophy, Brad Schoenfeld, PhD, CSCS, the world’s foremost muscle-growth researcher, concludes that while the entire rectus abdominis will be worked during exercises that target it, it is also possible to emphasize recruitment of the upper abs over the lower abs, and vice versa.

He writes: “Although somewhat speculative, there is a sound rationale for performing traditional crunch variations to target the upper abdominal region and performing reverse crunch variations to develop the lower aspect of the muscle… Not only do the tendinous intersections [of the rectus abdominis] suggest some degree of functional independence of the muscle, but its upper and lower aspects are segmentally innervated by the ventral rami of the lower six or seven thoracic nerves, providing a further mechanism for selective activation.”

Schoenfeld goes on to cite pro tennis players whose abs are bigger on their non-dominant side, which he says indicates that people can, to some degree, recruit not only the upper and lower abs selectively, but also the sides of the muscle.

Long story short: you can target different areas of the abs to shape them according to your goals, but you’ll never be able to isolate any one area of the muscle completely while turning off another one.

What’s The Difference Between Situps and Crunches?

Before we go any further, we should clarify some terms. If ab training really comes down to situp and crunch-type movements, let’s define what these are.

For many years, the situp was the primary ab exercise. You lie on your back with knees bent, and raise your upper body off the floor and up to your knees. This works the entire abdominal area, but it also recruits the legs and hip flexors, and it can be hard on the lower back (as we’ll examine in the next section). In the past few decades, trainers began recommending crunches in place of the situp—a more isolated movement for the rectus abdominis that requires you only lift your head and shoulders off the floor. It’s the safer, more targeted ab workout option between the two, but crunching alone won’t get you a six pack. These days, it seems best to favor crunches over situps, but perform them with different tools—such as a cable machine, stability ball, or inclined bench—to get more muscle activation without sacrificing safety.

Is It Safe To Do Situps and Crunches?

Whether you’re trying to work upper abs, lower abs, or both, the standard prescription is to perform some kind of spinal flexion exercise—i.e. situps or crunches—because bending the spine is a major function of the rectus abdominis.

In recent years, however, some athletes and trainers have contended that repeatedly bending the spine over time can lead to lower-back injury, including disc prolapse or herniation. The idea is that bending the spine pinches the intervertebral discs, gradually pushing them backward until they bulge out and press against a nerve, causing pain. While situp and crunch exercises may not cause back problems entirely on their own, they could throw gas on a fire that’s already burning in many athletes and recreational lifters. If you’ve been following a program that includes regular back squats and deadlifts, which compress the spine, and your lifestyle includes a lot of sitting and slouching (spinal flexion), you can understand how the concern arose.

For these reasons, some experts recommend developing the abs using only variations of the plank exercise, where the ribs and pelvis are held still and the rectus abdominis, along with the other core muscles, contracts isometrically. Schoenfeld agrees that well-chosen plank exercises can effectively train both the upper and lower abs, but argues that there’s nothing inherently dangerous with spinal flexion exercises either, assuming you’re not already contending with a back issue. In a review he co-authored, Schoenfeld determined that, if an individual has no pre-existing back problems, spinal flexion exercises are not only safe when done as normally prescribed, but probably necessary for maximizing development of the rectus abdominis. If you have aspirations of competing in a physique show, where your opponents will surely have well-defined abs, you’ll probably have to do some spinal flexion exercises to get the ab development needed to keep up with them.

For abs that look great and perform well, including having the ability to protect your back, healthy people should probably perform both planks and spinal flexion. Schoenfeld and spinal-flexion critics do agree, however, that too much spinal flexion isn’t good for anyone. If you’re old-school and think that 100 crunches or situps every day is the only way to see results, you could be setting yourself up for injury. Whatever the ab exercises you choose, they should be performed with moderate sets and reps like training any other muscle, with time off for recovery afterward. (We’ll give more specific recommendations below.)

Tips for Isolating Your Upper Abs

Just to recap, you can’t completely isolate your upper or lower abs, but you can emphasize one section over the other with different exercises and careful technique. To lock in on the upper abs, “You want exercises that are going to bring your ribcage down toward your hips,” says Jonny Catanzano, an IFBB pro bodybuilder and owner of Tailored Health Coaching, a fitness coaching service (@tailoredhealthcoaching on Instagram).

This means crunch/situp motions of all kinds, generally starting with your spine straight and finishing where it’s fully flexed at the lumbar. Yes, that means you’ll be rounded in your lower back, which is a major no-no for most loaded exercises such as squats and deadlifts, where the spine has to be kept neutral for safety’s sake. But to fully activate your abs, you have to take them through a full range of motion, and that means crunching your body into a tight ball. If you have lower-back pain, you may want to skip these kinds of exercises and do plank variations (we have a good one for you below), but otherwise, a few sets done two or three times a week shouldn’t present a problem.

Perform your crunch exercises for moderate sets and reps (2–4 sets of 6–15, generally speaking); don’t train them heavy. This will help to prevent placing unnecessary stress on the lower back.

To get the most out of your upper abs, “Squeeze your glutes to tilt your pelvis back, so your tailbone tucks under you when you begin a rep,” says Catanzano. Called a posterior pelvic tilt, this helps take your hip flexor muscles out of the exercise, so that your abs do the majority of the crunching.

What Exercises Work Your Upper Abs?

(See 00:52 in the video.)

A study by the American Council on Exercise showed that, out of 15 exercises tested, crunches done on a stability ball—as well as reverse crunches done on an inclined surface—both worked the upper abs the hardest, and nearly equally. (Incidentally, the reverse crunch on the incline also ranked highest for lower-ab activation.)

But don’t take these findings as gospel. Only 16 subjects participated, and two of them weren’t counted because they didn’t complete the study. Still, the results do suggest that you’d be smart to include crunches done on both a stability ball and an inclined bench in your program, provided you can do them safely.

In addition to those two moves, Catanzano recommends the following.

Kneeling Cable Crunch

(See 01:00 in the video.)

This exercise isolates the upper abs as much as possible, and the cable ensures that there’s tension on the muscles even when the spine is extended (where they would normally rest in a crunch done on the floor). The cable stack also makes it easy to increase the load as you get stronger. Use a V-grip to go heavier, or a rope handle for greater range of motion.

Step 1. Attach a V-grip or rope handle to the top pulley of a cable station, and grasp it with both hands. Kneel on the floor a foot or so in front of the cable so that you have to reach forward a bit with your hands to grasp the handle, and you feel a stretch on your abs. You may want to place a towel or mat under your knees for comfort.

Step 2. Squeeze your glutes and tuck your tailbone under so your lower back rounds a bit and you feel your abs engage. Crunch down, pulling the cable down behind your head as you bring your ribs to your pelvis. When your abs are fully contracted, that’s the end of the range of motion. Slowly return to the starting position. That’s one rep.

Don’t get carried away with the weight you’re using. It should never be so heavy that it pulls you up off the floor at the top of each rep.

Seated Pulley Crunch

(See 01:47 in the video.)

Performing a cable crunch on a lat pulldown machine may be a more comfortable option than the kneeling cable crunch, as it makes it easier to keep your hips stable.

Step 1. Attach a lat-pulldown bar to the pulley of a lat-pulldown station and sit on the seat facing away from the machine. Reach overhead and grasp the bar with hands shoulder-width apart and palms facing behind you.

Step 2. Squeeze your glutes and tuck your tailbone under so your lower back rounds a bit and you feel your abs engage. Crunch down, pulling the cable down behind your head as you bring your ribs to your pelvis. When your abs are fully contracted, that’s the end of the range of motion. Slowly return to the starting position. That’s one rep.

Hanging Leg or Knee Raise

(See 02:29 in the video.)

The pelvis flexes toward the ribs on this one, so it’s a good lower-ab move too, but it will hit the upper part of the rectus abdominis as well. Doing the movement with legs extended creates a longer lever and puts more tension on the muscles, but that will be too advanced for many people. If that’s the case for you, performing the motion with knees bent (a hanging knee raise) is a good modification. In either case, Catanzano warns that you don’t just lift your legs/knees. “That just works the hip flexors,” he says. “Make sure you bring your hips all the way up,” rounding your back as you do so.

Step 1. Hang from a pullup bar with your palms facing forward or toward each other. You may want to use lifting straps to reinforce your grip, so your hands don’t tire before your abs do.

Step 2. Tuck your tailbone under and raise your legs up, keeping your knees as straight as you can until your abs are fully contracted. Control the motion as you lower your legs back down. That’s one rep.

For the hanging knee raise, perform the same movement, but keep your knees bent 90 degrees the whole time. On either exercise, be careful not to swing your legs up or let them swing behind you at the bottom. You want your abs to do the lifting, not momentum, and swinging can strain your lower back.

Crossover Crunch

(See 03:52 in the video.)

Here’s an upper-ab exercise that also hits the obliques, the muscles on your sides that help you bend and twist.

Step 1. Lie on your back on the floor with your arms extended 90 degrees from your sides. Raise your right leg straight overhead, and then twist your hips to the left, resting your right leg on the floor. Cup the back of your head with your right hand.

Step 2. Crunch your torso off the floor and toward your right leg. Hold the top position for a second, and then return to the floor. That’s one rep. Complete your reps, and then repeat on the opposite side.

Pushup Plank with Tailbone Tucked

(See 04:45 in the video.)

If crunching movements aggravate your lower back, try plank exercises instead. Catanzano likes the classic yoga plank done a little differently—with the tailbone tucked under and knees bent to work the rectus abdominis more.

Step 1. Get into pushup position. Squeeze your glutes and tuck your tailbone under to activate your abs. Bend your knees and arms a bit so you feel like your midsection is hollowed out—abs braced, preventing your lower back from sagging.

Step 2. Hold the position for time. Aim for 30 seconds to start.

Your upper abs may get sore just from reading all this, but don’t make the mistake of thinking that training alone will produce a six pack. Exercise builds the ab muscles, but only a healthy diet can lower your body fat levels enough to reveal them, so if your belly currently hangs over your belt line, cut calories from your meals. Catanzano says that most men aren’t able to see ab definition until their body fat is in the range of 8–12%, and women need to be 14–18%.

See this guide on how to diet for abs.

How To Stretch Before Working Your Abs

Catanzano offers the following mobility drills for preparing your midsection for a session of ab training. Perform 10–12 reps for each exercise in turn, and repeat for 2–3 total sets of each.

Walking Knee Hug

Step 1. Stand tall and take a step forward, raising one knee to your chest as high as you can. As the knee rises, grab hold of your shin with both hands and pull it into your chest for a deep glute and inner-thigh stretch. Avoid slouching or bending forward as you do. Try to keep the support leg straight as well.

Step 2. Release the leg, plant your foot, and repeat on the opposite leg, walking forward with each rep.

Bird Dog

Step 1. Get on all fours with your hands under your shoulders and your knees under your hips. Tuck your tailbone so that your pelvis is perpendicular to your spine, draw your ribs down, and brace your core.

Step 2. Extend your right arm and left leg at the same time while maintaining your tight core. Don’t let your back arch. (Think about reaching forward with the arm and leg, not just raising them up.) Lower back down, and repeat on the opposite side. Each arm and leg raise is one rep.

Prone Scorpion

Step 1. Lie facedown on the floor and reach your arms out to your sides. Tuck your tailbone so that your pelvis is perpendicular to your spine, draw your ribs down, and brace your core.

Step 2. Raise your right leg up and reach it across toward your left arm. Reverse the motion and repeat on the other side. A touch on each side is one rep.

Prone Cobra

Step 1. Lie facedown on the floor with your hands on the floor at shoulder level, as in the bottom of a pushup.

Step 2. Press your hands into the floor as you extend your spine and raise your torso off the floor. Hold the top a second, and then return to the floor. That’s one rep.

Windmill Lunge

Step 1. Step forward and lower your body into a lunge. Extend your arms 90 degrees out to your sides.

Step 2. Twist your torso away from the front leg until it’s 90 degrees, with one arm reaching in front of you and the other behind. Come back to the starting position, and then repeat on the opposite leg, twisting and reaching in the other direction. Each lunge is one rep.

The Ultimate Upper-Ab Workout

Below are two sample ab workouts, courtesy of Catanzano, that you can add at the beginning or end of your current sessions, or on an off day. Alternate between the two workouts (A and B) for no more than three total ab workouts in a week. They’ll both work the entire abdominal region, but will emphasize the upper part of the rectus abdominis.

Workout A

1. Kneeling Cable Crunch

Sets: 3 Reps: 12–15

2. Hanging Leg or Knee Raise

Sets: 3 Reps: 6–12

3. Pushup Plank with Tailbone Tucked

Sets: 3 Reps: Hold 30 seconds

Workout B

Perform exercises 2A and 2B as a superset. So you’ll do one set of 2A and then one set of 2B before resting. Rest, and repeat until all sets are completed for both exercises.

1. Crossover Crunch

Sets: 3 Reps: 12–15

2A. Hanging Knee Raise

Sets: 3 Reps: 12

2B. Pushup Plank with Tailbone Tucked

Sets: 3 Reps: Hold 30 seconds

3. Seated Pulley Crunch

Sets: 3 Reps: 12–15

]]>

Bodyweight training is all about the basics and the truth is, no matter how advanced you are, your body will always fall back on its base level of strength. Your overall bodyweight strength will always serve as the foundation and bridge to your other strengths.

When it comes to the basics of bodyweight training, you should be familiar with all of the essential movements: squats, lunges, push ups, pull ups, rows, and plank variations. You should also have the ability to climb, crawl, sprint, and jump. These are primal movements.

Obviously there are hundreds, if not thousands of different variations for each of the basic bodyweight training movements out there, but no matter what, all of them come back to being able to perform the basics.

Bodyweight training serves as your foundation and is the driver of all of your other strengths and skills. Strength tools such as kettlebells, dumbbells, barbells, and sandbags are useless without having the proper bodyweight strength and conditioning foundation.

One of my biggest pet peeves is when young athletes or new clients come into my gym and they get frustrated when I don’t quickly put them under a heavy barbell to see how much weight they can lift.

Most of my clients (and even advanced athletes) have HORRIBLE form and technique when they first come in; this is totally normal, and quite frankly, all too common.